Splotter Spellen have built a reputation for creating games that are heavy, brutal at times, and often look and feel like a prototype. Horseless Carriage reinforces that reputation, but does so with a step up in terms of the quality of the components. I don’t like to focus on the quality of the bits in a box when it comes to a game, but it’s worth highlighting here because we’re not just dealing with a box of cards and cardboard squares this time. Horseless Carriage feels premium, which is great, but boy is there a lot going on. Maybe too much, I’m still on the fence, but I think I might love it.

Jumbled jalopy

Horseless Carriage is set back at the dawn of the automobile. Back when car designers were still deciding what needed to be on a car. Brakes, for instance, weren’t necessarily seen as a necessity. The main part of the game sees you laying out your factory floors in a tight, congested tile-placement problem. Each of your mainlines (the spots on the factory floor where the cars are assembled) needs to be connected to a station where a thing is added to it. Doors, brakes, engines, radiators – even the paint job – these can all be added to the cars you create if you can link them orthogonally to the correct side of a mainline. Each station can be connected to multiple mainlines too, if you manage to link to them.

The problem you’ll very quickly learn is that space on the factory floor is very limited. It can be really tricky to find the space you need. Space optimisation and planning is crucial. Not just important – crucial. Delbert Wilkins levels of crucial (ask your parents). The real kick in the teeth is knowing that once you’ve decided what goes where in the factory, you cannot move it. Not ever. Nor can you remove something to make space for something else. Once something’s bolted down it stays there. At the end of each planning phase you have to add another extension board to your factory, which just presents you with another set of tough choices while you decide which direction you want to expand into.

Each piece you add to a car is colour-coded, with each colour representing a selling feature, like reliability, safety etc. Different customers of the sales board demand different numbers of each feature, so to make the big bucks you need to make sure your cars deliver enough of those features. It’s not enough to just to make the cars, you also need to market and sell them too. How do you do this? You add dealerships and marketing departments. The fly in the ointment is that dealerships need to be adjacent to a mainline too, but dealerships are big and take up lots of space. Space that you want to use for stations to add things to your cars.

If you think games like Isle of Cats, A Feast For Odin, or even Barenpark are tricky tile-placement puzzles, then you ain’t seen nothing yet. Horseless Carriage is a harsh, unforgiving mistress. Too harsh? Depends how much you like agonising over every single placement you make. The factories feel so small sometimes. It’s less ‘knife fight in a phone booth’ and more ‘just-in-time supply chain and logistics in a phone booth’.

Brain not fried yet? We can fix that.

The spatial planning of the factory could genuinely be a game on its own. It’s not far off from what’s happening in Fit To Print (review here) for the entire game. As you might expect though, this is Splotter, and they’ve got a few more tricks up their sleeve.

The biggest part of the shared main board is the Market Board which represents your potential customers and their demands. Some of the spaces are populated by a neutral deck, but each player gets to choose where new demand will spring from in each round of the game too. Customers’ x and y positions on the grid indicate their demand based on the the current spec axes for the round. In one round you might have people who just want a little reliability and safety, while in the next their might be people who insist on higher standards for the cars’ range and design. Your own factory’s production is measured by how many features matching these specs you can deliver, so there’s plenty of foresight required when you conduct research.

Oh yeah, research. Another part of the puzzle. You can add research depts to your boards to move your company’s marker up each of the spec tracks, increasing the variety of stations you can add to your factory, hopefully meeting market demand later in the game. There’s a shared track on the main board which represents two ends of a scale. If you’re on the left of it at the Engineering end you get first dibs when it comes to choosing from the limited stations on offer to make your cars. You also get to use technologies which players other than you have researched, which is pretty awesome. You could even spend your own research points on moving someone else’s markers, just because you know you’ll have access to it.

The other end of that track is for Sales. The further to the right you are on it, the sooner you get to sell your Wacky Races cars to the unsuspecting public. Demand is limited, so getting the first chance to sell to the people who want the most expensive cars can be really important. A double-edged blade and no mistake. Do you make the most of everyone else’s research and build your own awesome KITT car from Knight Rider, but risk only being able to sell them for buttons? Saving and spending the Gantt charts (again, produced in yet another station) your factory makes is the only way to influence your order in the track. It’s easy to overlook how important this is, but you’ll only make that mistake once.

Fiddlier than fixing a faulty fuse on a faithful Ford Focus

Horseless Carriage has a staggering number of pieces. 92 cards might not sound like a lot, but couple that with the nearly 500 wooden pieces, and then add the 629 cardboard pieces that you’ll have to punch from 19(!) sheets of punchboard, and you get an idea of what I’m talking about. Just setting the game up to play means making stacks and stacks of station tiles, and when you get further in the later reaches of the game the market board will be swimming with little wooden cars. In addition to this your factory boards start to spread and swamp your own bit of space at the table.

When your factories get really complex towards the end of the game you need to be so careful to not bump the table, or let your clothes brush across it as you reach across the board for something. It’s all too easy to act like your own personal Godzilla and lay waste to all your hard work, destroying your factory’s layout. The station tiles just sit atop thin, card factory boards. There’s nothing to keep them in place. I’ve honestly taken photos later in the game just so I can use them to rebuild the factories in case they get moved.

The same is true of the market board. All those little wooden cars wouldn’t be an issue if it weren’t for the market windows. These are thin, really nicely made (by Splotter standards) plastic frames that you drop onto the market board to indicate where your customers will come from. They look great and do the job, but they’re difficult to manouevre and take back off the board without bumping and moving the cars, which are packed tight in the squares.

My final moan about all of this stuff is the spec boards. Each player has a wooden piece showing how far they’ve researched that thing, but with each new round one of these boards has to be moved away from the main board, and a replacement brought in. It’s too easy to bump one and send the pieces sliding, which again can be a real problem if you don’t know where everyone was on each board.

It’s all just an unnecessary distraction during a game which will already strain your mental aptitude to its limits.

Final thoughts

Horseless Carriage is a really tricky game for me to try to deliver a verdict on. I love a heavy, complicated game with interlocking gears and mechanisms, but at times this one almost feels like too much. The puzzle of filling the factory floor is really enjoyable, but tracing which thing connects to which other thing, making sure all the relevant tech markers are in the right place, and ascertaining what specs your finished cars have can be hard work. When you get it right, which takes time, it’s a deeply satisfying experience. When you get it wrong and realise you’ve stuffed up your chances of building anything decent until you get more factory boards in the following rounds, it can be really disheartening. That’s Splotter though, right? You know what you were getting into when you sat down to play.

The sheer amount of stuff in the box is just incredible. Good luck trying to get it all back in the box and have the lid shut flush. There are nowhere near enough baggies provided, which doesn’t help. I even ordered a set of trays to organise it from Cube4Me (who are excellent, by the way) and it’s still as ready to burst as my shirt buttons after Christmas dinner. If you want to play it before you buy, you can play an excellent version over on onlineboardgamers.com.

Horseless Carriage is a game which, with the right group of people, is an amazing experience. It’s heavy, it’s complex, there’s plenty of meta stuff happening with turn order and waiting to see who does what, and what’s left over, much like in Food Chain Magnate. Even after four plays I still don’t think I’ve scratched the surface of the strategy available in the game, but I can’t claim that as fact. It’s just the feeling I get from having seen how different each game has developed. The intro game where you all just build cars is a good way to learn, but it really comes to life when you add in the mainlines for trucks and sports cars too.

The part of the game which is the most fun is also the biggest deviation from the hard-fought, interactive nature of the game. Building your factory is cool, but it results in an intensely quiet period of the game where everyone has their head down, concentrating, and occasionally swearing under their breath. It’s not until everyone comes up for air and you see the results of all that planning and hard work that the interaction springs to life. Could that have been avoided? Probably not. It’s a game that takes the push and shove of FCM and throws in a geometric puzzle that’ll leave your brain in bits.

If you don’t enjoy heavy games, especially ones that’ll drag you over the coals the first couple of times you play, you won’t have a good time with Horseless Carriage. If you can invest the time and effort and have a group who dig that sort of thing too, you’ll be hard-pressed to find something better. A very clever game, an excellent game which asks its players to invest in it to truly appreciate it.

You can buy this game from my retail partner, Kienda. Remember to sign-up for your account at kienda.co.uk/punchboard for a 5% discount on your first order of £60 or more.

Enjoying this article? Consider supporting me.

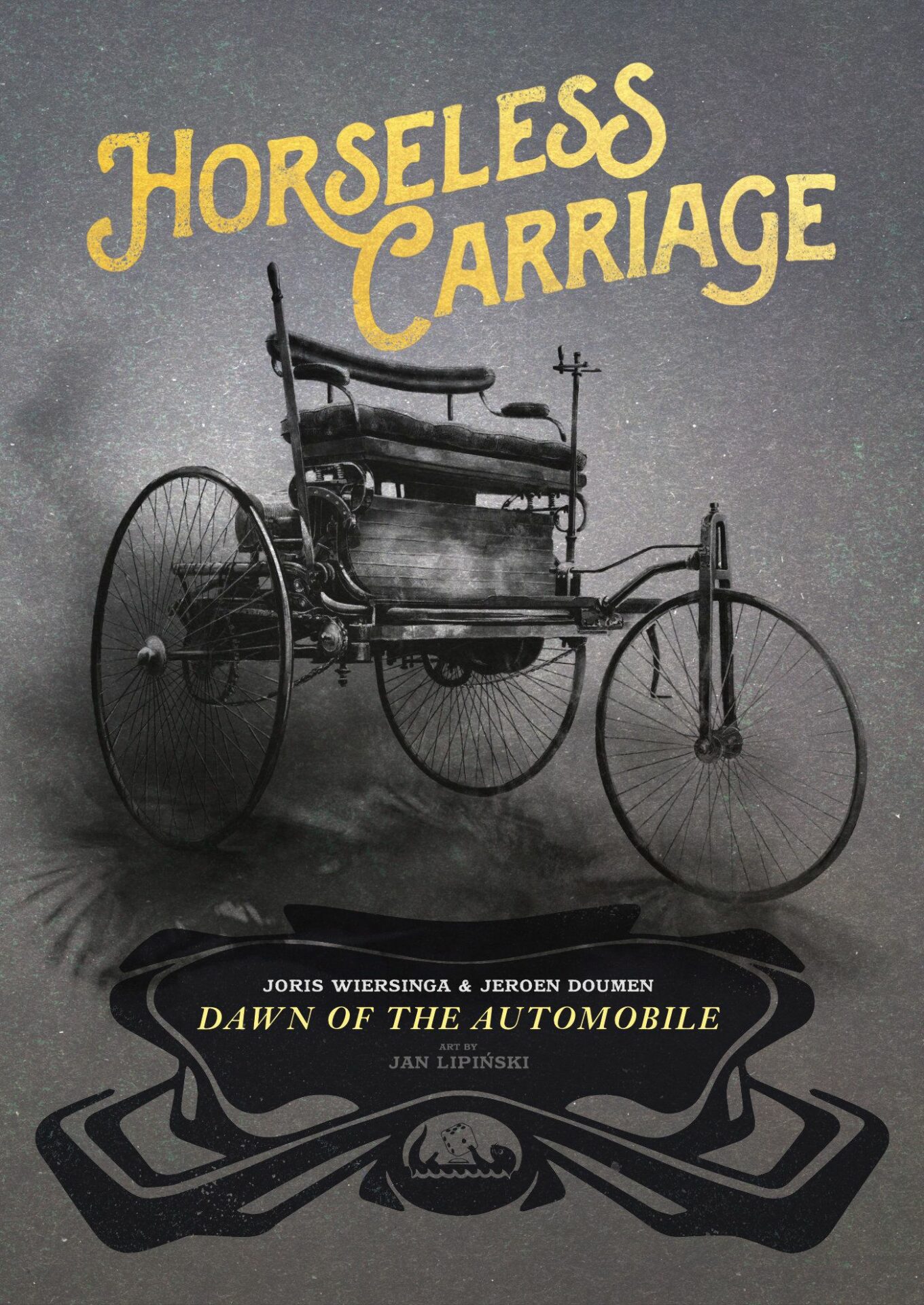

Horseless Carriage (2023)

Design: Jeroen Doumen, Joris Wiersinga

Publisher: Splotter Spellen

Art: Jan Lipiński

Players: 3-5

Playing time: 180-240 mins

Adam is a board game critic with over 15 years of experience in the hobby. A semi-regular contributor to Tabletop Gaming Magazine and other publications, he specialises in heavyweight Euro games, indie card games and transparency in board game media.