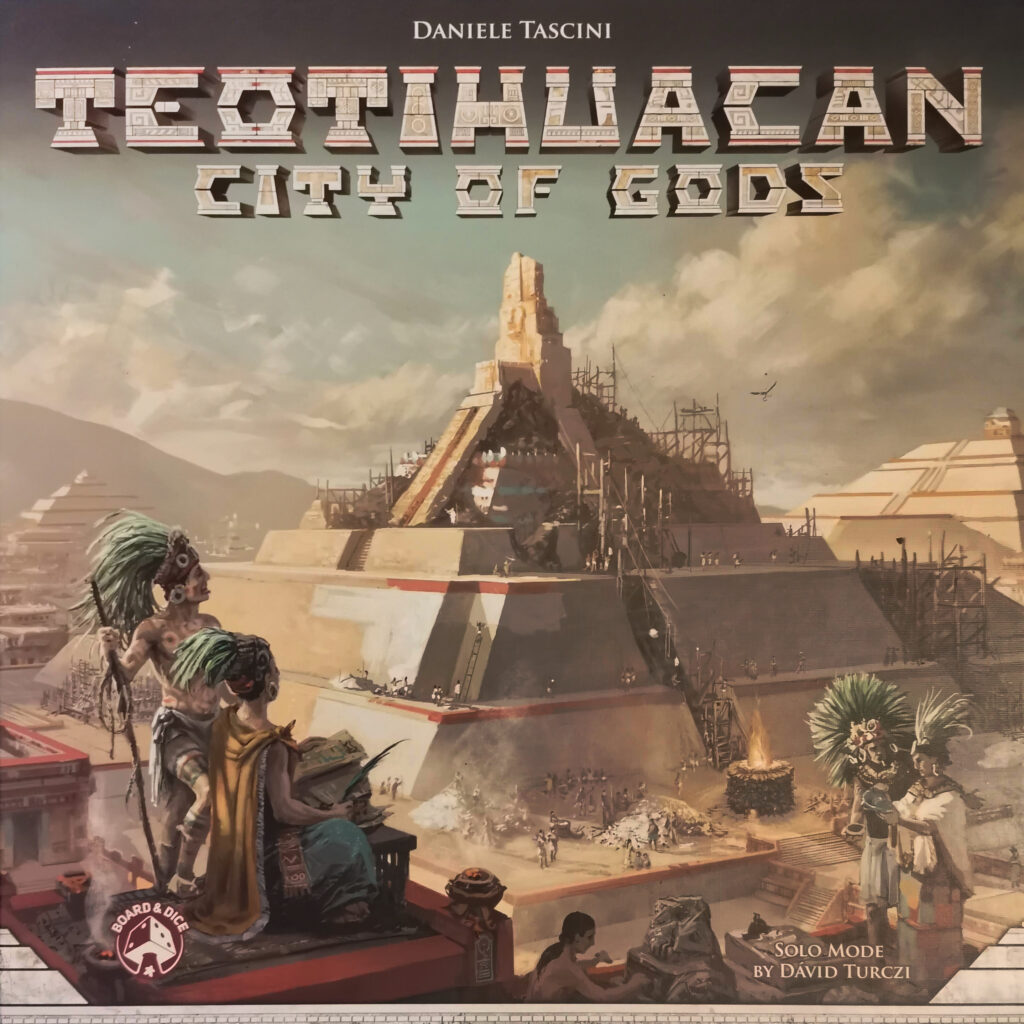

What’s special about Teotihuacan? Lots of Eurogames give you the feeling of building something. In Nusfjord you could be building industry in your village, or maybe you’re expanding the various shops available in Lords of Waterdeep. Some games even have you collecting the resources for it, like Hamburgum which sees you even buying little bells for the cathedrals you’re building. But how many let you physically build something magnificent, right there on the board?

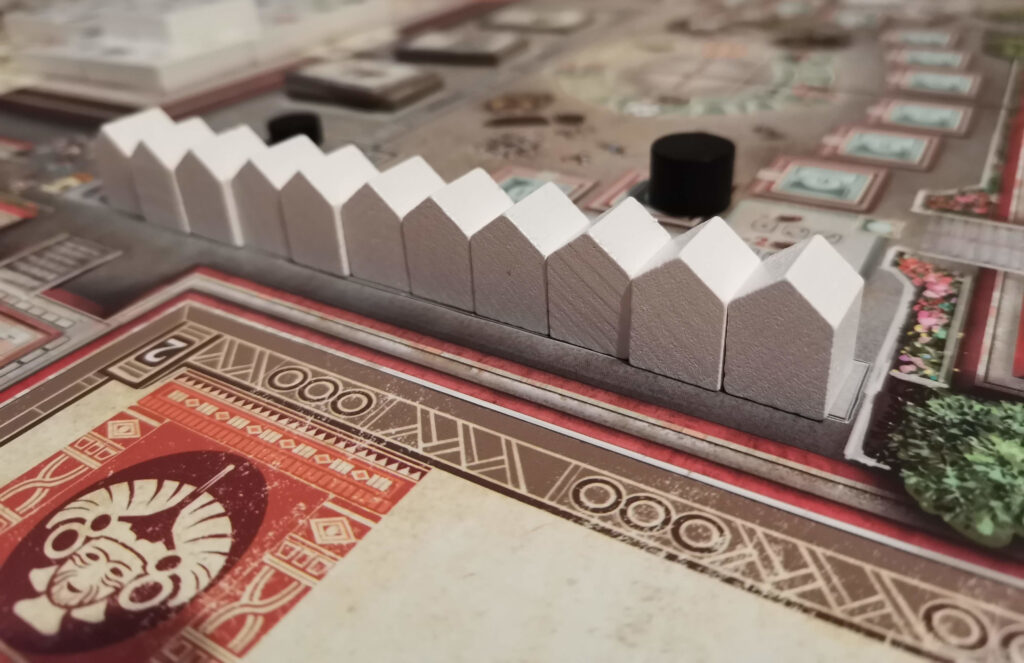

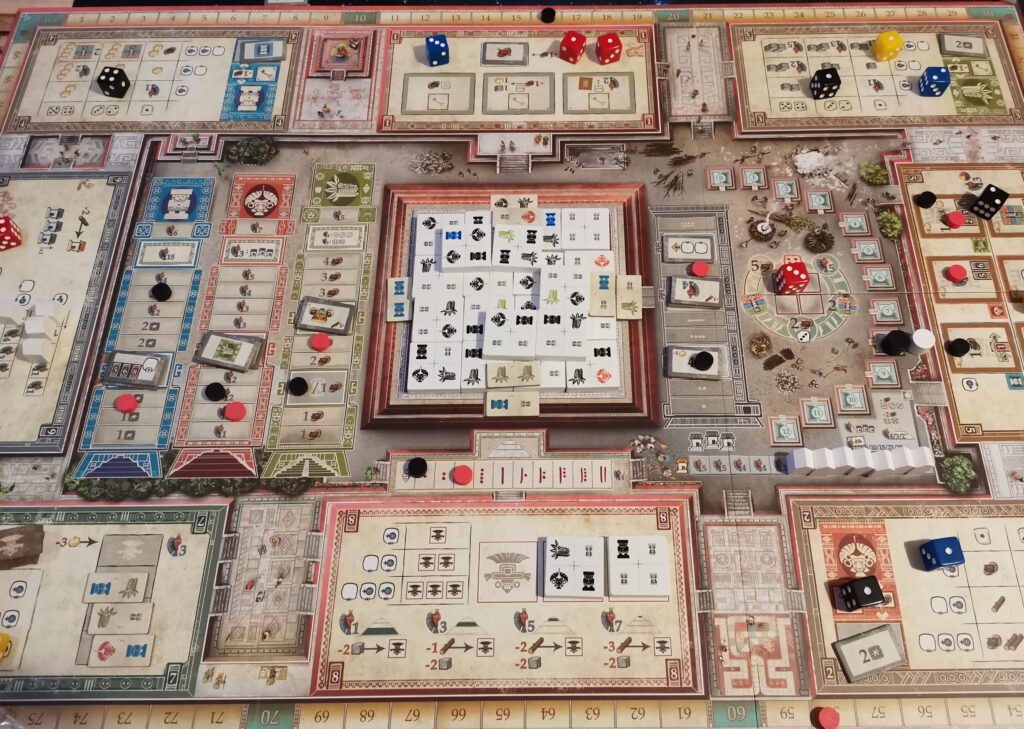

If you answered “not many” to the question above, then I agree with you. Games normally use tiles or cards to represent buildings. but Teotihuacan lets you build a pyramid out of chunky tiles, and even decorate it too. Right there on your very own table! Is there more to the game than a gimmick and eye candy though? Read on, and find out.

A Pyramid Scheme?

Players represent noble families constructing the Aztec city of Teotihuacan. To win the game you have to accrue the most victory points through constructing the great pyramid, advancing along the impressive, and real, Avenue of the Dead, and advancing favour with the gods at the various temples. To do this you need to place workers around the city’s sites, competing with the other players for resources, technologies, and making sure you have enough of the currency of the day, cocoa.

What’s In The Box?

As well as those gloriously chunky and satisfying pyramid tiles I mentioned above, there’s a lot of stuff in the box. The game plays up to four players, and each player has four dice which act as workers, so there’s 16 coloured dice in there. There are some nice wooden resource pieces for wood, stone and gold, although the wood feels a bit small and thin compared to the others. The board is like the one in Nemo’s War, it unfolds to six times its folded size.

Other than that there are a lot of cardboard tiles for all kinds of things; discovery tiles which are picked up all around the board for bonuses, decoration tiles to add to the pyramid for VPs, and starting tiles which give the players a choice of what to start each game with. Then there are action boards, technology tiles, royal tiles and temple tiles, all of which are optional but increase the longevity of the game. More on this later. The rule book is really clearly written and isn’t too long, so it’s nice and easy to jump around to reference sections of it.

How To Play

Teotihuacan is undoubtedly a Eurogame. There’s almost no interaction with other players other than taking tiles they might want, or forcing them to spend more cocoa than they’d like on an action. You collect resources and spend them on things to earn you victory points. It’s pretty unique in how strong the theme is, but it ticks all the Eurogame boxes. Normally when you look at a Euro though it’s pretty easy to say ‘that’s a worker placement game’, or ‘this is a card drafting game’. With Teotihuacan though, it’s not that simple, as we’ll soon see.

Getting Started

To start with the board is setup as per the rulebook, and all players draft a couple of starting tiles. These starting tiles show them which resources or advancements they’ll start with, and which areas their workers begin in. All players then take three dice, and these dice act as their workers.

So it’s a worker placement game then, right?

Yes, well, no. Kind of. In a normal worker placement game, players take turns choosing where to place workers, sometimes sharing a space, sometimes blocking it, but they can normally place them wherever they want. In Teotihuacan, in order to place a worker in a space to take an action, you take them from wherever they currently are, and move them between one and three spaces clockwise around the board, like a rondel.

Ah, so it’s a rondel game.

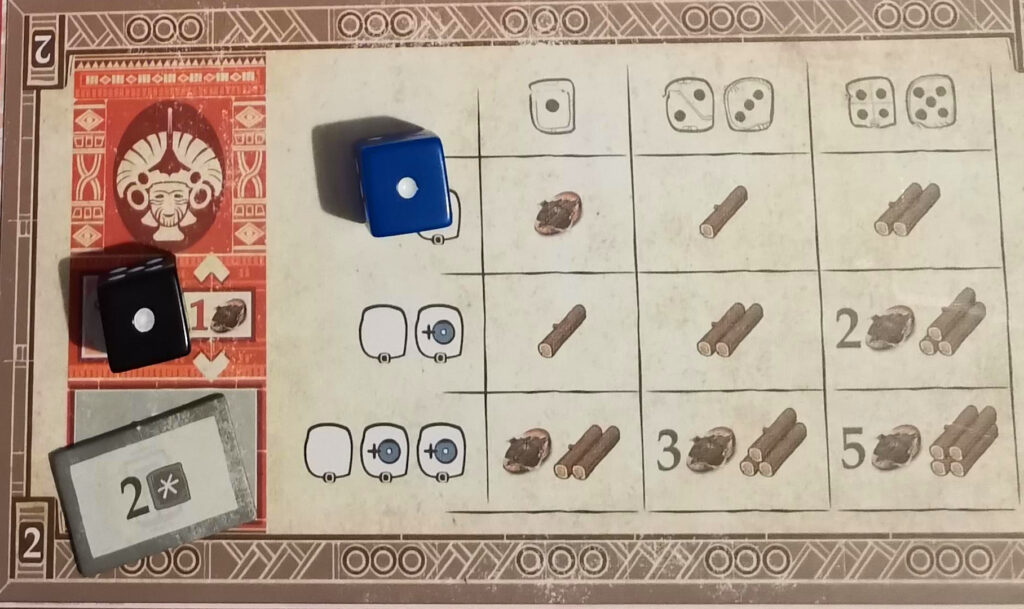

Again, yes and no. Normally in a game where a rondel determines your actions, what you get as a reward is fairly obvious. In Teotihuacan, things are different. Your workers start with the 1 pip on the die facing upwards, showing them as a level one worker. When they carry out a main action, they power up, and you rotate the die so that the next number is face-up. On every action space there’s a table of information which explains what you can do and what you get for carrying out that action.

Production

Let’s take the Forest space for example.

What this table tells me, is that looking at the top row, if I have a level one worker who carries out an action, I get a cocoa. If it’s level two or three, I get a piece of wood. And it the worker is level four or five, I get two pieces of wood. So far so good. But what happens if I already have a worker in that space?

In that example, I look at the second row down, and when choose which column I’m looking at, I pick the value of my lowest worker there Think of it like training the new guy. So if I have a five and a one, I still get the reward from the first column, in this case just one wood. So you can see, planning who will be where is a really important strategy.

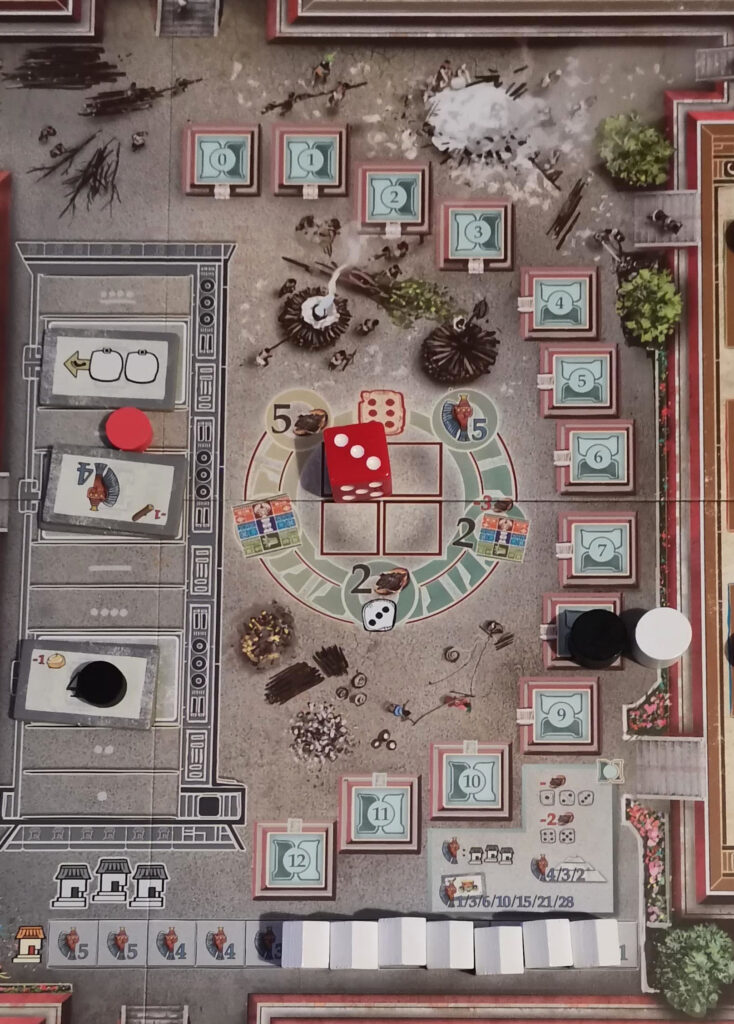

After your worker(s) take an action, one or more of them level-up, depending on how many were in the space, and if they reach level six, they ascend. “What’s an ascension?” I hear you ask. Although it’s never explained explicitly in the rules, it’s essentially a worker dying and being replaced (or maybe reincarnated) with a new worker. They rotate back to 1 pip on the die and are placed on the Palace area of the board. With that ascension you gain a reward from the ascension wheel on the board, which could be some VPs, movement up a temple track, cocoa, or even an additional worker. You also move your marker up one space on the Avenue of the Dead, which was a miles-long road in the real city of Teotihuacan, but in this game is one of the tracks to advance up.

Tracks

Lots of games have a track or two to progress along in search of riches and victory points. Teotihaucan boasts no less than six of them. Six!

Firstly there’s the Avenue of the Dead. One of your markers advances up the avenue every time you place a building on the Nobles area of the board, or one of your workers ascends. There are discovery tiles alone the way as rewards for getting there first, and at each eclipse, which act as round ends, players score based on their position.

Right next to the Avenue of the Dead there’s the calendar track. The white marker moves towards the black one at the end of each full turn, and trigger eclipses when they move past it.

Next there’s the pyramid track. Players move along the track one space for every tile or decoration tile they add to the pyramid. The player furthest ahead at the end of the round gets a bonus, everyone multiplies their position by an amount, and the positions on the track reset.

Finally we have the three temple tracks: blue, red and green. Certain discoveries and actions reward you with movement up one of the temples. You get a reward for every step, and along the way there are bonus discovery tiles to claim. Players who make it to the top of a track can expect big bonuses at the end of the game.

Cocoa

Cocoa is the currency of choice in Teotihuacan. The richest player will have chocolate pouring out of their pockets, probably. Cocoa is spent on certain discoveries, paying for actions, and paying your workers during an eclipse. Why you pay them in an eclipse I’m not sure, maybe direct sunlight spoils the cocoa?

If you want to take an action and other players are there, you pay one cocoa per different colour dice in that space. So if there were two black and one yellow dice there, my red worker would have to pay two cocoa. During an eclipse you have to pay your workers to the tune of one cocoa each, and one additional for every worker at level four or above. If you don’t have enough to pay them, it’s bad news, and it’s a three VP penalty per cocoa you can’t afford.

Various technology upgrades can grant you cocoa, and some discovery tiles. You can even take a five cocoa bonus when you ascend, but the usual way to accrue more is with a Collect Cocoa action. If you move your worker to a space with other players’ workers on, you can claim one cocoa per other colour, and one extra. So in the example above with two black and one yellow dice in the space, I would get three cocoa (two colours + one extra).

Worshipping

The final way to use your workers is to worship. Some of the main action spaces have a worhsip space. You can place your worker there to claim the discovery tile that’s there, to advance on the relevant coloured temple for the space you’re in, or pay a cocoa and do both. That worker is then locked. When a worker is locked they cannot move again, and you can’t use them until they are unlocked. To unlock a worker you either spend three cocoa during your turn to unlock all of your locked workers, skip your turn to unlock them for free, or wait for someone else to forcibly evict you from the space, paying you in the process.

Eclipses

The final thing to mention in terms of the flow of the game is the calendar track. At one end there’s a block representing the sun, at the other, one representing the moon. Whenever the last player completes a turn, or a worker ascends, the sun tracker moves down towards the moon. If at any point that movement would take it past, it’s the end of the round and there’s an eclipse scoring phase.

During the eclipse players score for their positions on the pyramid track and the avenue of the dead, and then pay their workers either in cocoa or cold, hard VPs. At the end of the third eclipse, the game ends, and the player with the most VPs when the dust has settled, wins.

Final Thoughts

Game mechanics are a dark art. The very best designers can take a mechanic and create a game that uses that mechanic beautifully, as Uwe Rosenberg does with worker placement (Nusfjord, A Feast For Odin, Fields of Arle). Attempts to mix them can have very mixed results however, as Flotilla proves in my opinion. The combination of hand management, tile placing, pick up and deliver, rondels, asymmetric play and more besides sounds like it could be Eurogame nirvana. Unfortunately it comes across as unwieldly and disjointed. So on the surface, Teotihuacan could have been a mess to play.

Thankfully, it’s a brilliant game. It’s a heavy game, for certain, but a brilliant one at the same time. There is so much going on at any one time, and so many options open to you on every turn, that on your first play you can feel swamped. One of the most basic choices is one of the most important – do you keep your workers close together to get loads of resources, or do you spread them around the board to always be close to a space which can give you what you need elsewhere on the board?

After the first game, when the pieces of the jigsaw start to fit together, it’s absolutely compelling. It takes quite a few more plays before you even get close to seeing the whole picture. I love the fact that with the exception of the piles of discovery tiles (which you can look through and pick from when claiming one), there’s no hidden information in the game. You can see what level each players’ workers are, you can see how many resources everyone has, you can see how close to the next eclipse you are, and where everyone sits on the advancement tracks.

Replay Value

Playing Teotihuacan is playing a big puzzle, one which is constantly changing. In my experience, games can be very close when the scores are totalled, so every VP feels important. When you think you’re getting close to solving that puzzle, finding an optimised way to play, you can open the other bags in the box and change things up a little. There’s a whole set of action boards which can be placed over the originals, which change where things are. This means that your learned routine of ‘start here, get this, then move there’ goes straight in the bin. The same goes for the technology tiles, which are bonuses you can buy with an ongoing effect. And again with the Palace tiles, and the temple tracks. There are so many ways to keep this game fresh without even looking at one of the expansions.

I highly recommend Teotihuacan to anyone with an interest in Eurogames who isn’t scared of spending a game learning how the pieces fit together. Daniele Tascini has created a masterpiece of subtly blending mechanics to deliver a rich, thematic, ever-changing experience.

Solo

Designer Dávid Turczi was brought in to add a solo mode, and it works really well. The execution is even thematic, with the AI player’s moves determined by shifting tiles around in a pyramid shape. The difficulty level is adjustable in small steps if you want to make it slightly easier, or harder. Personally I’ve been using a digital version available here, which just makes the game play slightly faster, without changing it. If you don’t have a fan of heavy Euros nearby, solo is a great option which means you won’t miss out on what is primarily a game of multiplayer solitaire.

Adam is a board game critic with over 15 years of experience in the hobby. A semi-regular contributor to Tabletop Gaming Magazine and other publications, he specialises in heavyweight Euro games, indie card games and transparency in board game media.